Elvia Rosa Castro

Translation into English: Anthony DeVincentis

To graduate with a Master’s in Dance Theory, Mercedes Ruíz wrote a brilliant thesis. In said study, she examined the nature of the cuerpo-tumbo (which in English might be rendered as “beat-body”), an image of her own invention; a figure so apt, precise, and poetic, that I am sure we will return to it for decades upon decades. Although Mercedes draws from her experience in the performing arts, and while this cuerpo-tumbo has a prior academic formation (as a trained dancer, for example), against which she rebels and of which she disposes, the image is so on the mark that, like all good theory, it can be brought to bear on other artistic practices.

Take this quote that explains the arenas in which this body performs:

“El cuerpo–tumbo genera sus escenarios que, en su mayoría, son espacios no tradicionales, nómadas, itinerantes, lugares en desuso que se pueden convertir en espacios creativos, casas, talleres, almacenes (espacios de precariedad), que pueden llegar a personalizarse. Se puede posesionar de manera autónoma, y son proyectos que no precisan del andamiaje teatral tradicional. Aunque, para existir, necesita un mínimo de condiciones, su existencia no está condicionada por infraestructura productiva. Su sensibilidad ejecutiva desemboca en una práctica travesti, anti-divista, capaz de gestar un cuerpo que se autogestiona todo su devenir escénico desde perspectivas hipertélicas, múltiples”.

“The cuerpo-tumbo creates its stages, the majority of which are non-traditional, nomadic, itinerant spaces, places in disuse that can be converted into creative spaces, houses, workshops, warehouses (places of scarcity), that can become personalized. It can be autonomously possessed, and its projects do not require a traditional theatrical framework. Though, in order to exist, it needs some minimum conditions to be met, its existence is not conditioned by productive infrastructure. Its executive sensibility results in a travesti (drag), anti-diva practice, capable of developing a body that self-manages its entire theatrical becoming from multiple, hyperlexic perspectives.”

One of the most emphatic characteristics of the cuerpo-tumbo figure is its autonomy. As for the term “tumba,” its colloquial, imperative use in Spanish (meaning sal de aquí, vete de aquí, or beat it; get out in English, hence the translation “beat-body”) implies an expulsion, an exile that compels one towards autonomy and predisposes one to self-direction. The cuerpo-tumbo dissents from a customarily established canonical tradition and practice. One intuits that there’s a great deal of artivism embedded in that image.

From the moment in 2019 that I had access to Mercedes’ first notes I sensed that much of Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara’s work could be observed from such a perspective and that he, in and of himself, was a projection of that cuerpo-tumbo: his independent development, his artistic and later political dissidence. His knowledge of how to manage—to take advantage—of space as an act of piracy—as he himself described his actions in years past, as he takes control of other stages and situations in an opportunist fashion: the street, the streets of Por aquí no pasó el Papa, those of the pilgrimage with the Virgin, the performance in the Manzana de Gómez Hotel …This marks the second occasion in which I mention the term “pirate” to speak about Luisma using his own words, and perhaps it needs clarification.

In a written statement from 2011 explaining the series Reciclaje y resistencia, he asserts: “Mi obra consiste en aprovechar el marco donde una vez aparecieron esculturas ambientales transitorias y el papel importante que jugaron en el público, para mediante un homenaje a los autores y a la memoria colectiva, intervenir con esculturas que semejan dichas obras utilizando materiales madera, tela…”

“My work consists of taking advantage of the pedestals where there were once temporary public sculptures and of the important role they played in public space in order to make an intervention, through an homage to authors and to collective memory, with sculptures that resemble the former works utilizing materials such as wood, fabric…”

Stripping away the canon, literally. His queer-ish (half-queer) cheekiness to intercede in it. But above all I related the notion of the cuerpo-tumbo with LMOA via the Dionysiac idea of frenzy (non-rest, non-cessation). Seen in this way, the cuerpo-tumbo is the body of artivism. It is the body that passes from insolence to a certain humility, and that in the face of the hedonistic training of the gymnast prefers to cultivate affect. Because one of the keys of artivism lies in empathy. Artivism possesses a strong link with conceptualism but also contains a heavy dose of affection and empathy that is projected on the level of the individual: Artivistically speaking, you cannot be successful if you’re not charismatic, “un buena gente” (a good person), a person of confidence, first and foremost, in your neighborhood, in your community. This is not to say that there’s no intellectual excellence or that all rests entirely in the hands of an essential, intuitive direction. The artivist’s conceptual growth is spurred through studies of local and community history, of laws, legality, institutional practices, and demands a keen political awareness. The effectiveness of the artivist’s creation-direction is also dependent on an organic link with other types of knowledge and forms of expression: music, poetry, law, criticism and post-criticism, without a precedence in practice for any one notion of superiority. This is clear in the practices of INSTAR (1) but above all in the very genesis of the Movimiento San Isidro, plural and diverse.

As artivism emerges where there is “desalojo y expolio” (eviction and dispossession) it cannot, as a matter of morals, repeat the very frame of action that brought it about. In the face of exclusionary binarism and machocentrismo (androcentrism), it proposes an insecure and tender ego, whose only robustness lies in the legitimacy of its denunciation, in the organic nature of its agenda: the right to have rights.

The first of Luis Manuel Otero’s pieces that I saw were shown to me by Juanito Delgado, in 2011; he had them in his house on the Malecón. They were these exceedingly droll wood sculptures that were selling like hotcakes which Luisma called “mis muñecos de palo” (my stick-Action figures). He referred to them in this way fondly, but also to undermine any elitist commentary. The use of precarious materials, found in their “pure” state given that he applied neither patina nor sandpaper, and their “impure” state given that the material is charged with histories and experiences; the vindication of Arte Povera (once again, this is a cycle) are elements we also see in his more procedural and heavily conceptual efforts, as well as in his gestures and actions. But above all, there are particular aspects that I would like to emphasize: spontaneity (“reactive gesture,” as I called it), freshness, and impertinence, along with the deeply somatic charge of his work. Look well and you will see that almost the entirety of his oeuvre is volatile and vulnerable, susceptible to being violated and vandalized. In short, it’s him. There is much of his body, with all the weight that it implies, in everything that LMOA has ever created, not just in his most well-known performances such as Drappeau, and Miss Bienal, but also in his pilgrimages, in his ¡artivismo, por tu vida! (artivism, oh dear!)… Ergo, there is a lot of gesture too: ambiance and temporal events.

Nevertheless, not all is pure intuition and sixth sense. There are no loose ends in his works. With his launch of the now celebrated “estamos conectados” (we are connected; we are online) we do not glean solely the existence of webs of affection and empathy, much less the technical matter of having internet access; it indicates that it’s in position at the ready for denunciation. The phrase “estamos conectados” is key in the development of activism and is effective at any latitude. To be connected is to be ready and willing.

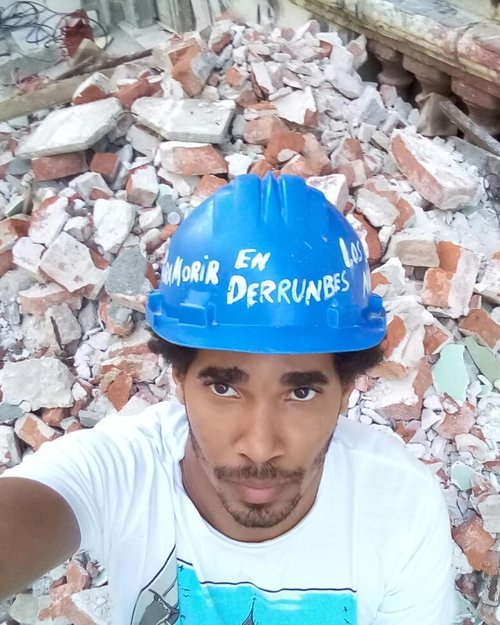

The Papa piece, Súper Pijo, the work about Mella, the raffle to win a night at the Manzana Hotel, the helmet performance calling attention to the girls’ deaths in La Habana Vieja, the Garrote Vil, or the exquisite Chong Chon Gang exhibit this connection: and when each work, such as these, emerges from contingency and an apparent contextual arbitrarity, that reactive, chemical component comes about, which can be appreciated in their gestures. 100% adrenaline. La Bienal 00 and the very emergence of MSI, while they are highly organic, come about through this reaction to contextual arbitrariness and exclusion. Luisma has a sixth sense for opportunity. And it’s through this, his timeliness, that we see a near lack of mediation, which makes the works even more forceful. In their gestures, just as in their chemistry, there’s an overwhelming notion of the present and of presence, as with all performance art. As a result, all of his work is structurally linked to this artistic practice, even when it’s not overt.

On August 11th of 2021, LMOA launched a civic participation project Proyecto Carta de Renuncia. It declared: “El objetivo de este proyecto es poner a disposición de Díaz Canel un total de 10 cartas para que él elija una y renuncie a la presidencia de Cuba para facilitar/acelerar la transición de poder en la isla, co-creando un espacio de imaginación colectiva” (This project’s objective is to place a total of 10 letters at Díaz Canel’s disposal so that he may select one and renounce the presidency of Cuba in order to facilitate/accelerate the transition of power on the island, co-creating a space of collective imagination.) Luis Manuel takes as his premise the writer Jules Verne’s conjecture when he thought up the not-yet-invented submarine. He follows the course of those calculations that secretly conduct our being and wonders: does that which slumbers behind the eyes exist?

The convocation that Luisma commenced from prison can be grasped through the realm of gesture and with a sense of opportunity. Titled Proyecto Carta de Renuncia, Luis Manuel concocts a fiction with hints of futurology, as in Otro tratado de París (2018). Yahweh appeared before Moses, Alexander before Diogenes, the Pope before Tania Bruguera, and Fidel before Luisma. The artivist-leader possesses a charm that magnetizes the criticized leader and, at the same time, the latter requires his presence. It’s a perverse magnetism, at that. The artivist is the medium through which power is scrutinized. In other words, the politician always tries to swallow up the artivist first because he admires him, and second, in order to neutralize him. In Otro tratado de París Fidel apologizes before the Cubans through a video hidden in a flash memory which only Luisma could access, and finished his address with “patria y vida” (2).

In this summons Luisma offers social media users the opportunity to write a letter playing the role of Díaz Canel. In both, the need to create a distinct parallel reality, a ficta thinking of what is to come, is essential.

In Proyecto Carta de Renuncia Luis Manuel distances himself from his guerilla and theatrical practices in order to bestow upon social media users a means that was hitherto prohibited: the individual’s voice can speak directly to and hold sway over power. Letter #16, written by Cubano Insurrecto is a gem. This piece not only foresees or gives a prognosis for a possible stage in Cuban political reality, but it also, like all effective art, allows for individual catharsis and solace grounded in life experiences, both personal and collective. This participatory exercise is fundamental even in sociological and epistemological terms. We have, in this anthology of missives, material from which to observe how far Cubans have come in terms of political culture.

When an artivist hands over the microphone, the pencil, or any implement to other hands in order to remake, to culminate an action, etcetera, etcetera, it means that they’re in tune with the nature of their practice. To be a point of intersection. There is no superiority in artivism, the ego registers zero decibels. In artivism, all that is shifted to the affective stage and in this way the notion of compassion and religare enter the field of art.

The artivist can be an outsider or they can come from the political or cultural elite but in both cases they are victims of prior censorship and are troubled by a profound malaise. They hail from the periphery or from the margins as seen from the central X perspective, and they’re quite vulnerable. “El poder desprecia a todos los artistas por igual” (Power despises all artists equally). Radicalization begins with the recognition of this truth. The institution wants nothing to do with the artivist because firstly, they speaks to it in tongues, and the institution—all of which are strictly conservative—suffers vertigo; secondly, they removes it from its comfort zone. Exterior to itself the bureaucratic entity does not know how to function. Instead of trying to understand the new cultural logic, it feigns ignorance and casts it out. At that point condemnation and discrediting begins. The sin of the artist is never of her own doing, it’s of the institutional incapacity to reset itself.

The most beneficial course is always to threaten the “normalized space” protected by institutional mediations. We must keep in mind that such a space—regulated, zombified, stupefied—means the trivialization of our lives and creates the mirage that all is well. That unimaginative and deranged bubble is more violent than the very artivist that fights against it, and puts it in check once in a while.

Notes:

(1) Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt (Hannah Arendt Artivism Institute; INSTAR) is a Cuban organization that describes itself as “a living organ, which breathes, feels, reacts, and remembers,” and grew out of a 2015 performance piece by Tania Bruguera, who would go on to direct INSTAR. Citing 915 founding members, the institute was conceived as a “democratic and horizontal space,” interested in political and human rights, social justice, and free expression in Cuba, and offers events, resources, and residencies for Cuban artists while focusing on three structural objectives: to be an incubator for desires, ideas, and actions that bring about civic literacy (instar.org).

(2) Patria y vida, which has become a rallying cry for political transformation and social justice among Cubans on and off the island, was popularized by a 2021 song and music video of the same name released by Yotuel, Beatriz Luengo, Descemer Bueno, Gente de Zona, Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, Maykel Osorbo and El Funky. As in Otro tratado de París, the phrase references Fidel Castro’s infamous credo “patria o muerte” (homeland or death, in English) and counters it, calling for “homeland and life,” or more figuratively translated: “my country and my life.”

*Text originally published in Spanish in El Estornudo.

More info about #Luisma in the following links:

https://www.e-flux.com/journal/118/398435/the-artist-as-hostage-luis-manuel-otero-alcntara/

Related

Related posts

2 Comments

Leave a ReplyCancel reply

Estamos en Twitter

Top Posts & Pages

- Blog

- PRIMER AVISO (SUFRE HAROLD BLOOM)

- CARLOS QUINTANA: SOMBRA Y SUSTANCIA

- EL HUMANISTA LOGOTIPO DE LA BUNDESLIGA

- Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas y el ARTE REDENTOR

- JOSEFINA TARAFA EN LA FREEDOM TOWER

- SEVERO SARDUY: ASÍ NO SE TEMPLÓ EL ACERO

- TERESA MARGOLLES: LA MUERTE ES BELLA

- RETRATO DE ARCHE*

- OBRA DE LA SEMANA XXXVI

Recent Posts

To find out more, including how to control cookies, see here: Cookie Policy

[…] Tania. Un evento sin precedentes cuyo impacto se replicaría posteriormente en sondas infinitas con Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara y el Movimiento San […]

[…] del occidental. Para ello quisiera referirme a las propuestas de Julio Huayamave, Carlos Vargas, Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, Marianela Orozco, y Los Carpinteros. Los dos primeros ecuatorianos, específicamente […]